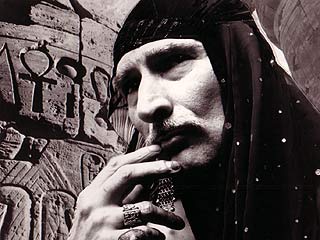

Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis, Mary Jordan’s absorbing documentary portrait of the legendary filmmaker and performer, certainly gives a strong flavor of this underground artist, whose importance never really has been disputed within avant-garde circles, even if he’s not a household name or nearly as famous as many of the other major artists he influenced, including Andy Warhol, John Waters, or the Italian director Federico Fellini.

Jack Smith (1932-1989) led a very troubled life. Smith was born in Columbus, Ohio. His mother, who married three times, moved to Galveston, Texas and then to Kenosha, Wisconsin. The film reveals that she left Jack and his sister, Sue Slater, alone for two weeks before the final relocation. It’s no wonder that Smith blamed his mother for sending him “crippled” out into the world. In a letter to her, which he recites in the film, he confesses, “I’m left with feelings of jealousy, mistrust of women, homosexuality, impotence.”

Jack Smith’s issues were not only with his mother, but with the world at large. A militant anarchist, the intensely political Smith railed against capitalism in the guise of “Landlordism” and “Lobsterism” – his own colorful vocabulary for “exploitation” – as the source of much of his own and society’s ills. A modern-day Proudhon, Smith couldn’t fathom either paying rent or art collecting – to him both were merely different forms of theft.

Smith vented against people and institutions for not supporting him in his artistic endeavors, believing that “real art” was destined to get “mutilated” within capitalist culture. He became famous for making one of the most notorious underground films of the 1960s, Flaming Creatures (1962) – a baroque, gender-bending orgy of naked and costumed bodies, which was busted and became a test case of censorship laws. The experience had a traumatic effect on both Jack Smith and his career. The reception of Flaming Creatures became a rationalization for his “never making any masterpieces again” or finishing any of his later films.

As a child, Smith became enthralled with the B-movie actress Maria Montez, who became a lifelong obsession. According to the composer John Zorn, Jack would cry whenever he watched her movies. The late playwright and Warhol screenwriter Ronald Tavel calls the actress a “diva,” while John Vaccaro refers to her as “the apotheosis of the drag queen.” Only filmmaker Nick Zedd counters that he couldn’t understand this adoration of Montez because she was such a “mediocre actress.” When Smith was dying in the hospital after deliberately contracting AIDS, Tavel suggests that rather than being bored, Jack was happy because it gave him more time to ruminate about Montez.

For Jack, Maria Montez represented the epitome of exotic glamour. To him, she became a fantastic imaginary world that replaced the ugly one in which he found himself. Smith turned the NYC loft where he lived for the last nine years of his life into a virtual fantasy land. The film provides a glimpse of Smith’s glorious inner life by tracking through what was in reality an elaborate and colorful stage set, which was dismantled and destroyed after his death.

Jack’s performances were notorious within the art world. He would announce that an event would begin at a certain prescribed time and then delay it for hours, causing many audience members to flee when nothing happened. Tavel suggests that Smith did this deliberately. He quotes Jack as saying, “I don’t want the scum of Baghdad. I want only the best.” The artist who insists that art should be made free to the masses turns out to be an elitist at heart. Jack Smith was full of contradictions, but his own response to the issue of audience was simply: “Something had to be done in order to keep them from becoming sofa-roosting cabbages.”

My only personal experience with Jack Smith was being invited to a small gathering at someone’s loft in the late 1970s where it was rumored that Jack was going to perform. Throughout the night, he made strange faces, glared at people suspiciously, periodically whispered in the host’s ear, and continually disappeared into a hall closet, where he seemed to rummage around for hours. Needless to say, Jack lived up to his reputation, and I finally left around midnight. Yet what he was actually doing could be construed as a weird performance of sorts.

Jack Smith’s personal animosity for Jonas Mekas became another major fixation. Smith despised Mekas for using Flaming Creatures as part of an anti-censorship crusade during the 1960s. Smith complains that Mekas could “be made to seem like a saint, to be in the position of defending something, when he’s really kicking it to death.” Ronald Tavel suggests that Mekas’s strategy was to make “as much money as possible from those films and give as little as possible to the filmmaker.”

Although Jonas appears in the film, it’s never clear that he’s ever responding to such charges, which is one of the unfortunate drawbacks of Jordan’s decision to make a heavily-edited compilation film. As far as information obtained from interviews, it’s simply not possible to understand either the questions or the context of the answers. In any event, I seriously doubt that there were buckets of money to be made from screening Flaming Creatures at the time, or that Jonas secretly was pocketing money that was owed to Smith.

Smith began to refer to Mekas by a variety of disparaging names, including “Uncle Fishhook.” Sylvère Lotringer helped to legitimize Jack’s personal attacks on Mekas in a 1978 issue of Semiotext(e). As Lotringer explains in Jordan’s film, Uncle Fishhook became a symbol of the system: “Uncle Fishhook became like this kind of embodiment of a myth that was so much bigger than Jonas Mekas could be.” Jack also had the bad habit of turning on people. Lotringer tells of hearing rumors that Jack was walking around the East Village with an ax and wanted to kill him.

There are plenty of published sources on the ongoing feud between Mekas and Jack Smith, but we never do get to hear Jonas’s side. There is an explanation for why Mekas withheld the original film of Flaming Creatures from Jack Smith once it came into his possession. As an archivist, Mekas wanted to preserve Jack’s legacy, especially because Smith would project and edit his originals during screenings that he turned into theatrical events. Is trying to save the original of Flaming Creatures such a bad thing? For Smith, it became part of a larger paranoid conspiracy in which he cast himself in the role of victim.

Jordan’s film also glorifies Jack Smith at the expense of Andy Warhol. As Nayland Blake rightly states: “So many contemporary artists trace their practice back to Warhol at this point, and a lot of the important ideas in Warhol come from Jack.” Robert Wilson indicates that Warhol couldn’t have made the films he did without having known Jack. John Waters claims of Jack Smith: “He did it all first. He started something that other people took and became more successful with.”

Lawrence Rinder, the museum curator and director, along with noted composer and filmmaker Tony Conrad, point to Warhol’s Factory and the whole notion of superstars as deriving from Jack Smith. Artist Mike Kelly mentions the fact that Warhol used Smith’s actors for his own films. Yet none of this is really news. Warhol, who watched films at the Filmmakers’ Cinemateque prior to making them, was influenced by many experimental filmmakers, including Kenneth Anger, Ron Rice, and Jack Smith. Warhol never denied his admiration for Smith’s work. Instead he indicates that Smith was “the only person I would ever copy” and adds, “I just think he makes the best movies.”

Jack Smith appeared in a number of Warhol films, including the unfinished Batman/Dracula (1964), Camp (1965), and Hedy (1966). George Kuchar points out that in Batman/Dracula, Warhol failed to record all of Jack Smith’s performance because of bad framing. Henry Hills and others claim that Smith took over Camp, where he managed to get Warhol to move his camera. Mekas suggests that the two artists clashed because Smith wanted to have complete control. If Smith was all about control, Warhol was the exact opposite – he was interested in abdicating authorial control.

Mario Montez, Jack’s drag-queen incarnation of Maria Montez, appeared in a number of Warhol films as well, which Smith didn’t appreciate. Like an overly protective parent, Jack Smith criticizes how Mario Montez was being employed by Warhol. While Smith never specifies a title, he seems to have in mind Screen Test # 2 (1965) when he laments: “I just hate to see this happening to Mario. Slowly watching Mario’s brain being eaten away . . .”

The schism between Smith and Warhol was personal, but also represents the difference between a baroque and pop sensibility. Smith had a trash aesthetic. His art was about making something beautiful out of nothing. Warhol used techniques of mass production in his art, hence the whole idea of The Factory, which enabled him to become an incredibly prolific artist. Jack Smith takes a direct swipe at Warhol when he suggests that “manufacturing and making art” are two different endeavors. Warhol obviously didn’t think so. Smith insists, “I want to be uncommercial film personified.” Warhol, on the other hand, always had commercial aspirations and made the fact that art was a business only too evident.

While the film certainly sides with Smith over Warhol, the film’s compilation technique allows it to move, for instance, from John Waters saying, “He [Jack Smith] was a great personality and a great filmmaker who changed everything” to someone claiming that “Jack Smith was the real Warhol.” Frankly, I find that to be an incredible leap. There is no question that Jack Smith exerted an enormous influence on Warhol, but what does it mean to say he was “the real Warhol?” In different voices of various interviewees, Jordan also edits fragments of the interviews into the hyperbolic assertion that Jack Smith reinvented theater, photography, film, performance art, glitter, installation art, time, and music videos.

Many notable artists get a chance to discuss Jack Smith and the brilliance of his work, which alone makes this film worth viewing. Voice critic J. Hoberman, who has written extensively on the work of Jack Smith, is sorely missing as an interviewee for reasons that have to do with the making of Jack Smith and the Destruction of Atlantis and issues related to Smith’s estate (For details, click here and here). And the inclusion of scholars, such as Callie Angell, might have provided the film with a more balanced perspective on Warhol.

Smith’s social critique extended to curators, museums, and foundations, whose real function he believed was “commercialization.” Only John Waters introduces a dose of reality into Jack Smith’s vilification of museums: “He bit every hand that could ever, ever feed him. And so, the problem is nobody knows his movies because of that. And he never finished them. And if he maybe had been a little less difficult, maybe we would have seen his movies more. They’re very obscure now. He bit the hand! Museums. . . who else is going to show them? It’s [sic] not going to play at Radio City Music Hall!”

Toward the end of the film, Smith makes a startling and rare admission about himself in terms of his artistic career: “It’s my fault. I haven’t been organized properly. . . I was never organized nearly enough. I didn’t know those things.” But, as Jack Smith insightfully points out, had he done all the things he should have done or that were expected of him, “I wouldn’t have been the same person.”