I talked about the identity crisis facing American independent cinema in my recent book on indie screenwriting. It’s been a topic of discussion almost from the start, as evidenced by Jonas Mekas’s criticism of the second “scripted” version of John Cassavetes’ Shadows as “just another Hollywood film.” Jon Jost’s premature declaration of the indie movement’s death in an article in Film Comment in 1989 would serve as another important historical marker, as would Ted Hope’s similar conclusions in a 1995 issue of Filmmaker. Sparked by the lack of emerging talent at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Sight & Sound’s April cover story also decries the cooption of a truly alternative practice.

There is, of course, much truth in Michael Atkinson’s largely cultural analysis of the phenomenon facing American independent filmmakers, in which he sees a shift from social interaction to self-absorption as a result of a preoccupation with new technologies. He writes: “Today, we are consumers first, citizens second, and the castle of distraction we’ve built around ourselves is itself little more than a series of revenue streams devised to exploit us.” In terms of a truly independent practice, Atkinson asks what is there to make films about when “everyone’s too comfortably busy being entertained, intoxicated, distracted and market-researched.” Yet he finds some glimmer of hope in the self-distributed work of David Lynch and Andrew Bujalski, along with filmmakers such as Gus Van Sant, Todd Solondz, Lodge Kerrigan, and Kelly Reichardt.

Despite her acknowledgement of some strong isolated features over the past several years, Amy Taubin contends that “only two US filmmakers – Richard Kelly and Andrew Bujalski – made me think they had a shot at having careers as significant as Todd Haynes, Richard Linklater, Gus Van Sant, Spike Lee, David Lynch or Jim Jarmusch.” Her email quote from Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha and Mutual Appreciation) seems a bit odd within the context of the Atkinson’s critique. Bujalski writes of his intention to shoot another small low budget project, suggesting that “as the unsustainability of this endeavor becomes more & more pressing it seems like I’ve got to make a small film now or never, certainly it would be harder to go ‘back’ if the studio project I’ve been hired onto comes to fruition.”

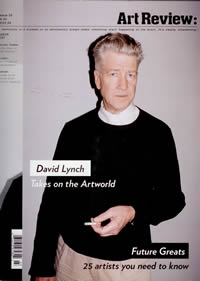

The mainstream film industry has the ability to co-opt independence, including Bujalski’s desire to make another small low-budget feature. Yet what’s not mentioned in Sight & Sound article is that there’s another alternative out there, namely the art world. One only has to go to a major gallery, art fair, museum, or biennial to realize that half of the work shown involves film or video in some form or another. While the big galleries have their own issues (which I shouldn’t minimize), the art world is at least a lot more willing to allow artists the freedom to realize their vision than executives of film companies. Artists such Matthew Barney, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Yang Fudong, Diana Thater, and Jane and Louise Wilson are striking examples. If Bill Viola, Pierre Huyghe, and Jesper Just can have galleries and museums commission large-budget projects, I easily could see David Lynch and Gus Van Sant receiving the same type of financing and by-passing the studios as well. Art magazines today are also writing about film in ways they haven’t before, so I’m not at all surprised to find David Lynch on the cover of the March issue of the highly influential Art Review with the heading: “David Lynch Takes on the Art World.” The article discusses his current show “The Air Is on Fire” at Foundation Cartier in Paris, which features work in a variety of media: painting, drawing, photography, installation, sound, and film.

The mainstream film industry has the ability to co-opt independence, including Bujalski’s desire to make another small low-budget feature. Yet what’s not mentioned in Sight & Sound article is that there’s another alternative out there, namely the art world. One only has to go to a major gallery, art fair, museum, or biennial to realize that half of the work shown involves film or video in some form or another. While the big galleries have their own issues (which I shouldn’t minimize), the art world is at least a lot more willing to allow artists the freedom to realize their vision than executives of film companies. Artists such Matthew Barney, Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Yang Fudong, Diana Thater, and Jane and Louise Wilson are striking examples. If Bill Viola, Pierre Huyghe, and Jesper Just can have galleries and museums commission large-budget projects, I easily could see David Lynch and Gus Van Sant receiving the same type of financing and by-passing the studios as well. Art magazines today are also writing about film in ways they haven’t before, so I’m not at all surprised to find David Lynch on the cover of the March issue of the highly influential Art Review with the heading: “David Lynch Takes on the Art World.” The article discusses his current show “The Air Is on Fire” at Foundation Cartier in Paris, which features work in a variety of media: painting, drawing, photography, installation, sound, and film.