Last September, Scott Tobias on the A.V. Club Blog pleaded for audiences to support the theatrical runs of Andrew Bujalski’s Mutual Appreciation (2005) and Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy (2006). He wrote: “If you care at all about American independent films, you’re required to see these movies.” Tobias concluded his post: “So vote with your dollars, people: If you want to see more movies like Mutual Appreciation and Old Joy, you have to create a viable market for them. Otherwise you’ll be left to hold out for Little Miss Sunshine 2.”

Tobias’s impassioned call-to-arms was met with equally spirited resistance. One lengthy comment from a suburban exhibitor responded that Bujalski’s Funny Ha Ha (2002) and Mutual Appreciation simply weren’t very good. He wrote: “On personal level, it depresses me how much critical attention these two films are receiving considering their level of mediocrity.” The Reeler chimed in on Old Joy: “In her readings of landscape and faces, Reichardt captures spatial and structural dynamics that her story just cannot support; even at 76 minutes, the film exhausts its premise and tension less than halfway through.” Despite such harsh criticism of Bujalski and Reichardt’s work, Mutual Appreciation and Old Joy wound up on many Top Ten film lists for 2006. In the indieWIRE national critics’ poll, Old Joy placed number 7, while Mutual Appreciation came in at number 20. Unfortunately, though, neither film did very well at the box office. According to boxofficemojo.com, Mutual Appreciation took in $103,509 domestically and $121,292 worldwide. Old Joy faired a bit better. It made $255,923 in its U.S. release, and a total of $301,047 worldwide.

One reason for being interested in Bujalski has to do with a resurgence of realism in recent American independent films. Realism often has been conceived of as an alternative to the staged contrivance of Hollywood film. One just has to go back to read Jonas Mekas’s early writings in Film Culture and the Village Voice to see that he championed the first version of Cassavetes’ Shadows, Frank and Leslie’s Pull My Daisy (1959), Ron Rice’s The Flower Thief (1960), and even the work of Andy Warhol precisely on these grounds. In my book, I cite numerous examples of the realist impulse providing an alternative strategy of narration in indie films, such as Jarmusch’s eschewal of plot, Haynes’s fractured dialogue in Safe mirroring real-life speech patterns, Van Sant’s use of real time and non-professional actors in Elephant, Slacker’s collapse of the relationship between performer and role, and Harmony Korine’s associational structure in Gummo. The rationale for realism always seems to be that it more closely mimics real life.

At the end of his Village Voice review of Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Hoberman writes: “Coming in the same year as Andrew Bujalski’s similarly understated and character-driven Mutual Appreciation, it attests to a new strain in Amerindie production – literate but not literary, crafted without ostentation, rooted in a specific place and devoted to small sensations.” Given Hoberman’s remarks, it might be interesting to compare Kelly Reichardt’s film about thirtysomethings with Mutual Appreciation, especially in terms of their use of realism. Like Gus Van Sant’s Mala Noche (1985), Old Joy is largely an accumulation of artfully composed visual images and sounds held together by a slight narrative. The film, for instance, begins with shots of nature. After the sounds of a meditation bell, a bird on a gutter flies off. We see Mark (Daniel London) meditating outside his house, followed by a shot of swarming ants.

At the end of his Village Voice review of Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Hoberman writes: “Coming in the same year as Andrew Bujalski’s similarly understated and character-driven Mutual Appreciation, it attests to a new strain in Amerindie production – literate but not literary, crafted without ostentation, rooted in a specific place and devoted to small sensations.” Given Hoberman’s remarks, it might be interesting to compare Kelly Reichardt’s film about thirtysomethings with Mutual Appreciation, especially in terms of their use of realism. Like Gus Van Sant’s Mala Noche (1985), Old Joy is largely an accumulation of artfully composed visual images and sounds held together by a slight narrative. The film, for instance, begins with shots of nature. After the sounds of a meditation bell, a bird on a gutter flies off. We see Mark (Daniel London) meditating outside his house, followed by a shot of swarming ants.

The tranquility to which Mark aspires is punctured by the loud grinding of an electric blender and the sound of music indoors, as his pregnant wife, Tanya, makes some type of green smoothie. The phone rings. The film cuts to Mark still meditating with the sounds of neighborhood kids in the background. The answering machine plays a message from his old friend Kurt, who announces he’s in town. Tanya comes into the room and stares at the answering machine. A pan over telephone lines to a bird creates a transition to Mark’s conversation. As Mark talks with Kurt, Tanya paces back and forth in the background. When she sits down, there’s obvious tension between them. Tanya resents Mark seeking her permission to go camping with Kurt, and the two of them argue briefly, suggesting either they have marital problems, which have become exacerbated by their impending baby, or that it’s directly connected to the message from Kurt. In general, Old Joy is all subtext. Everything that occurs in the film happens underneath the surface, which provides the narrative tension.

Although Old Joy is imbued with subtext, it’s not a film that’s strictly about personal relationships in the same sense that Bujalski’s films are. As Mark drives to meet Kurt, we hear Air America on the radio, which situates what transpires within a political and cultural context. Old Joy provides us with a sense of nature and physical place, not only as indicated by the opening scene but through long tracking shots of neighborhood and later extended shots of the natural landscape that convey the texture of the Pacific Northwest. As Mark reads the newspaper on the porch, Kurt yells: “Hey, man!” We see a wide shot in which Kurt (Will Oldham) pulls a red wagon holding a TV, as he walks toward him. Old Joy is at heart a portrait of two former buddies who represent a striking contrast in character. Oldham communicates through the awkwardness of his herky-jerky bodily movements, whereas we register Mark’s feelings largely through the anguish on London’s expressive face – he’s virtually a walking reaction shot. There’s not very much plot in Old Joy. The two friends go camping, get lost, spend the night camping in a garbage-strewn site, and eventually wind up in the hot springs in the Cascade Mountains. While Mark lies blissfully in the hot spring, Kurt gently massages his shoulders, the meaning of which (sexual or fraternal) is left open to interpretation.

Old Joy is ultimately about small moments. For Kurt and Mark, their camping trip represents a last-ditch attempt for these two old friends to try to reconnect before the trajectory of their lives sends them off in separate and irreconcilable directions. It’s about how people change (or don’t change) over time. Mark, for better or worse, has settled down into conventional responsibilities – job, marriage, and a family – whereas Kurt has chosen to remain a pot-smoking free spirit with no job or relationship or much in the way of a future. He represents stasis in a world that’s rapidly changing, as represented by the fact that Sid’s record store has closed and migrated to Ebay, countercultural values have been replaced by careerism, and even nature itself has become transformed into a cultural construct. Kurt is rapidly becoming an anachronism. Old Joy can be read as a look at this cultural transformation. It depicts a world view that’s being replaced by technological changes and by a new generation of young people, who are represented in Bujalski’s films.

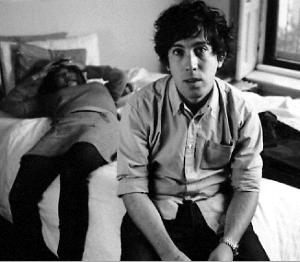

Mutual Appreciation also has very little plot. Like the shared intimate moment between Mark and Kurt, Ellie (Rachel Clift), however, verbalizes her fantasy to kiss Alan (Justin Rice), the Beatle-haired, band-member protagonist of the film, despite the fact that she’s in a relationship with Lawrence (Bujalski), a nerdy graduate teaching assistant. The film begins with Alan lying on the bed with Ellie after arriving in town to make it in the music scene. Alan goes on a radio show with an Asian-American DJ named Sara to promote his music. Sara aggressively puts the moves on him afterwards, but he politely resists, especially when her brother becomes a possible drummer for his band. After his band plays at a local club, Alan lets Sara know that he’s not romantically interested in her during an awkward scene in the kitchen. It seems that he’s still hung up on a previous girlfriend. Very drunk, Alan later allows three women to dress him in drag. Otherwise Alan has conversations with his father about his need for money, while his father worries that Alan’s not trying hard enough to find some type of real job that will enable him to pay his credit-card bills.

Even though Alan is the film’s protagonist, it is actually Ellie who has the dramatic conflict. She flirts with Alan throughout, often playing the role of interrogator in their conversations, largely because Alan is often too busy flashing a huge grin to initiate very much conversation on his own. Together they discuss creating a cool people club, and Alan even asks Ellie to be his band manager at one point. Ellie also counsels Alan to be less of a rock star and to be straight with Sara about his lack of interest in her. Ellie later decides to stay at her own place rather than Lawrence’s one night under the guise that she has to get up early for work the next morning. After driving Alan home, Ellie maneuvers her way inside to get a CD of his music, and then, as they sit on his bed, tells him her fantasy about wanting to kiss other guys, including him.

Nothing happens, but Ellie deliberately skips attending the wedding of Lawrence’s old girlfriend. Alan shows up at her work place. As they drive together, she confides that she feels excluded from the special bond that exists between Alan and Lawrence. The two share some type of intimacy afterwards. Ellie tells Lawrence what happened when he returns. Lawrence wonders why Ellie couldn’t have left it as an unspoken fantasy rather than bringing it out into the open. It also disturbs Lawrence because he saw it coming, but he instantly forgives her. Lawrence later brings up the incident with Alan, who insists that nothing really happened between him and Ellie other than the fact that they experienced a shared moment together. The three of them eventually have a group hug and collapse on the bed before the film abruptly ends.

Whereas Old Joy’s realism is both visual and poetic and concerned with landscape and place, Mutual Appreciation focuses almost exclusively on verbal interactions of its young characters. Although he has an interesting and varied way of staging scenes, Bujalski is not a visual stylist like Reichardt. Despite Hoberman’s suggestion that both Old Joy and Mutual Appreciation are rooted in a specific place, I don’t find that to be true of Bujalski’s film. New York is talked about, but the film could have been shot anywhere. Most of it takes place indoors. There are very few exterior shots, and the ones we see don’t evoke New York in any specific way. Like Old Joy, Bujalski’s film also operates through subtext. It takes awhile to figure out that Ellie has an infatuation with Alan, even though the clues are there from the very opening scene, in which the two lie on the bed together before Lawrence arrives home and plops himself between them.

It takes more than ten minutes of viewing to grasp the subtleties of Bujalski’s work. Like Warhol’s films, duration is important somehow. Bujalski’s performers are extremely charming and engaging as characters. No matter how inarticulate they might be, they all have a unique and idiosyncratic way of expressing themselves, a way of syncing up with each other’s body language that communicates to the viewer. Bujalski’s work, like Reichardt’s, gets better upon multiple viewings. The nuances become more apparent. Scenes unfold at their own leisurely pace, but Bujalski has a DJ’s sense of abruptly terminating a scene, just at the point where it gets most interesting. Even though his work is scripted, Bujalski’s non-professional performers have an ability to seem unpredictable in how they will say something, of making it sound like their own thoughts and words. They also have great sense of timing in terms of line delivery and reactions.

Bujalski’s cinema is one that’s centered on performance, but he also has the ability to create complex characterizations. One is often unclear of the ultimate direction of various scenes, but that unpredictability is what keeps us watching. There’s not the calculated arc to his scenes, nor does Bujalski seem very interested in dramatic situations, but he’s the master of creating very awkward or embarrassing ones. Obviously, this type of cinema, like Reichardt’s, may not be for everyone, but Bujalski has made two impressive features to date, and that’s no minor achievement.