So Yong Kim’s For Ellen (2012) begins with an illuminated directional road sign at night, followed by a close-up of the darkened face of Joby Taylor (Paul Dano) as rock music blasts from the car’s CD player. The image suddenly explodes into sharper focus when he lights the cigarette dangling from his mouth. As the exhausted rock musician tries to eat something the next morning after driving all night, the food falls into his lap, causing his car to swerve out of control on the snowy road. For Ellen is Kim’s third feature after In Between Days (2006) and Treeless Mountain (2009), two films that established her reputation as a major visual stylist and one of the most intriguing new American independent filmmakers working today. Like her earlier films, For Ellen explores the effects of the breakup of a family. In this case, it looks at a deadbeat dad, not as inexplicable absence and gaping hole in a daughter’s heart, as in In Between Days, but from his point of view.

The purpose of Joby Taylor’s long car trip soon becomes apparent, when he meets with lawyers and his estranged wife, Claire (Margarita Levieva), who is seeking a legal settlement and wishes to have no communication with him during the proceedings. He stammers, “We’re both adults now, right Claire? We can work this out.” When the signing is postponed for a day in order to give him more time to look over the court documents, Joby asks to have coffee with Claire, but she bluntly refuses. He follows her out to her car and tries to cajole her “for Ellen’s sake,” but, as Claire drives off, he shouts, “You fucking serious? Get the fuck out of here. I don’t even want to talk to you.” For emphasis, he kicks and spits at her car and curses at Claire.

Kim uses images and sound to convey Joby’s state of mind. For nearly a minute afterward, he sits in his car and appears to down some pills. This is followed by a shot of him checking into a motel, an extended wide shot of a couple of cars traversing the highway at dusk, an extreme close-up of his eye, a house fly, fragmented shots of his body, including his lips, before the fly crawls into his ear, causing him to jolt up in bed. It’s a sequence right out of a horror movie, but it might also be a reference to an early Yoko Ono and John Lennon film. With headphones on, Joby rocks out to music under the warm glow of incandescent light in his motel room. He plays pool at a local tavern and ends up embracing an attractive woman, followed by an exterior shot of a snowy field with trees and power lines in the background.

At a meeting with his inexperienced lawyer, Fred Butler (Jon Heder), the next morning, it soon becomes evident that Joby must sign over custody of his young daughter to receive a half-share of the house (for which he hasn’t actually made any payments). “You’re the lawyer,” he tells Fred in disbelief, “isn’t there something you can do.” He phones Claire and turns up at her house, where he spies Ellen inside and experiences pangs of guilt. He then calls Fred and insists that he needs to spend time with his daughter. He whines, “I mean . . . this is so unfair. Why does Claire get everything?”

The soft-spoken rock musician initially appears well-meaning. Like a child prone to temper tantrums, however, he has the capacity to explode into rage when he doesn’t get his way, first with Claire and then with a band member on the phone. As he paces outside his motel, Joby tells a fellow musician that he wants to “start re-tracking and add a little more heart to the songs.” He insists, “We need some real shit.” When the guy doesn’t buy it, Joby shouts into his cell phone: “You’re nothing without me. I’m the front man. I’m the fucking singer. What the fuck are you going to do without me? I’m fucking Joby Taylor. I am Snake Trouble. I started this fucking band. You don’t talk to me that way.” And he’s not beyond threatening Claire after she turns down his request to see Ellen.

Fred, who has picked up a copy of Joby’s first album at a yard sale, invites his client over to his house where his mother has cooked lasagna. She asks Joby a great many personal questions at dinner, causing discomfort. The awkwardness is momentarily broken when Joby invites Fred to go to a bar. After a beer and a couple of shots and a smoke outside, Joby suddenly breaks into a suggestive dance number and mouths Whitesnake’s “Still of the Night.” His rendition is so over the top and narcissistic that it freaks out the young lawyer. As Joby leans back a the bar as if nodding out, Fred asks him whether he’s okay, but Joby responds curtly, “Yes, I’m fine.” When Joby buries his head on the counter, Fred wonders whether he should call a cab, but the rocker snarls, “No I don’t want you to call a fucking cab. I want you to go.”

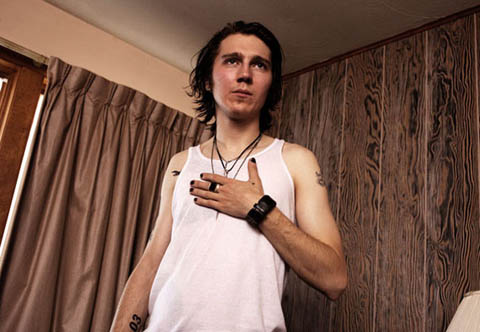

With its bizarre mood swings, the bar scene is one of the highlights of Kim’s film, especially in the way the erotic undercurrent of Joby’s rendition of the heavy metal song manages to seduce and repel at the same time. A master of the double message, Joby does eventually get to spend brief time with Ellen (Shaylena Mandigo) after he plays his trump card. During their visit, he talks to the sweet but skeptical child more like a nervous stranger than a parent. Although Joby tries to play the role of interested father, he doesn’t exactly fit the part. With his greasy hair, painted fingernails, hoodie, leather jacket, piercings, tattoos, and wisp of a goatee, Joby looks decidedly out of place in either a toy store or playground.

Kim’s painful and engaging For Ellen is a skeletal narrative with only a smidgen of plot. It’s essentially a character study that focuses almost entirely on Joby. You can see the appeal of the role for an accomplished actor like Dano – he’s virtually the whole show. It’s almost as if Kim, for whom the subject has personal relevance – she met her own father as a four-year-old when he showed up unexpectedly – is trying to fathom this character through the power of observation and by embedding him within the frozen landscape of the film’s setting.

Kim shoots Joby in extended takes, suggesting that if we watch him closely enough, he might suddenly reveal the mystery behind his self-absorbed behavior. Despite how often he looks at himself in mirrors throughout the film, Joby can’t really see himself. When he tells Ellen, “I want what’s best for you,” quite sadly we grasp that he’s confusing the pronoun.