Todd Haynes’s new feature I’m Not There is not the first film to have its protagonist played by multiple actors. Christopher Maclaine did it out of necessity in his early beat classic The Man Who Invented Gold (1957) when he had to take over the main role after two other performers quit. Todd Solondz also used eight different actors to play the young heroine of Palindromes, but the rationale behind the strategy remained pretty sketchy. That’s not the case in Todd Haynes’s brilliant portrait of Bob Dylan, which uses this tactic as a way to deconstruct the biopic.

Even a really good biopic, such as Anton Corbijn’s Control (2007), doesn’t offer much insight into the short-circuited life of Ian Curtis, the tortured lead signer of the band Joy Division. Epilepsy and an impulsive decision to marry while still a teenager and then have a child put Curtis in a straightjacket of his own devising, leading him to commit suicide when he was unable to reconcile the discrepancy between his own sense of self-righteousness and an adulterous affair. The film’s only recourse is to register the pained expression on Sam Riley’s face.

Such facile psychology often provides the motivation for characters not only in biopics, but in narrative films in general. Todd Haynes, for instance, refused to explain Carol White in Safe for this very reason. Haynes responded at the time: “It was very much a strategic plan on my part to try to exclude a lot of information that we usually think we require to know about a character in a film. What that meant was basically excluding the sense of psychological access to a character. When you look at the way we are made to feel secure about knowing a character in a movie, it’s so facile and silly – it’s such a short-hand way.”

With a celebrity personality like Bob Dylan, we only really know him through various mediated depictions. Todd Haynes utilizes the various personae of the man to present a composite if contradictory view of the singer. Some of his conceits are downright hilarious, such as having the early Dylan played by an eleven-year-old African-American boy (Marcus Carl Franklin) as a Woody Guthrie wannabe. There are six other Dylans presented by five other actors. Christian Bale plays the folk singer named Jack Rollins and later the born-again Dylan, Pastor John; Ben Whishaw performs an interview of Dylan as the poet Arthur Rimbaud; Heath Ledger plays Robbie, a movie actor and family man, while Richard Gere plays the reclusive Dylan as Billy the Kid in pastoral sequences from an earlier era involving Pat Garrett’s plans to destroy the town of Riddle, a place that perpetually celebrates Halloween.

If the sequences involving Gere don’t already feel like you’ve entered some Lynchian alternate universe or suddenly been transported into another movie, an ostrich appears and then a giraffe lopes into one of the shots, providing a sense of bizarre exhilaration. At other times in the film, Richie Havens plays music with the young Dylan on a back porch and a fictional Gorgeous George makes a cameo, along with embodiments of Joan Baez, Allen Ginsberg, a number of Black Panthers, and Moondog, the blind poet and musician who was a street fixture during this era, suggesting that Haynes has created his own Noah’s Ark of 1960s culture.

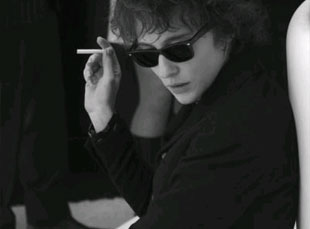

It is Cate Blanchett’s Dylan, Jude Quinn, however, who provides the glue that holds all the other sequences and elements together. Suffice it to say that her performance is extraordinary, even though her rendition of Dylan is the utterly hostile, bitter, and pretentious one we remember so well from D. A. Pennebaker’s unflattering documentary, Don’t Look Back (1967). Blanchett plays Dylan like a cocksure androgynous marionette, frolicking with the Beatles, verbally sparring with critics, provoking audiences to near riots, mercilessly ridiculing the Edie Sedgwick character, Coco Rivington, after their brief fling, and then castigating his friend and associate, presumably Bobby Neuwirth, who was also in love with her. “Love and sex are things that really hang everybody up,” Jude sneers, as if this banal cliche represents profundity.

To his credit, Haynes leaves out Andy Warhol, Dylan’s bête-noire during this same period. Their conflict over Edie was central in the biopic on her tumultuous life, Factory Girl (2006), a film that seems based on a CliffsNotes version of events. Although he’s not physically there, Warhol, in some strange way, nevertheless hovers likes a ghost over I’m Not There – a ghost behind a ghost, so to speak – because no one understood celebrity culture better than the Pop artist, and no one managed to expose the mass media as such a complete charade.

In fact, Blanchett’s Jude makes the fatal mistake of trying to fill the role celebrity culture demanded of him with disastrous personal consequences, whereas Warhol willfully took the role of con artist as both his personal identity and survival mechanism. If the notion of self as a social construction serves as the basic premise of this film, celebrity culture gives us the fake reassurance that we somehow know these people, while they often get lost in their own hall of distorting mirrors. As Haynes comments of Dylan: “He undermines the things you count on, your touchstones. He shakes up the things that people used to build their own selves on. Every time you grab onto him, he’s somewhere else. I thought the only way to do anything in a film about him would be to dramatize that fact, to use that as the sort of principle to organize the narrative, or many narratives.” Stuck in his own hagiography, Dylan had no real choice other than to mutate, which is something Ian Curtis failed to realize.

I’m Not There uses an associational structure that seamlessly weaves together these various representations of Dylan, moving freely back and forth in time. While the bad-boy scenes with Blanchett are perhaps the most riveting, Haynes manages to make us feel genuine sadness for Robbie’s wife, Claire, and his kids. There’s something about Claire’s acute attention to the children – her continual conversations with them – that creates a sense of the isolated life of a single parent, especially one abandoned by a celebrity partner. Even the way the kids gravitate to Robbie when he turns up at the house suggests where Haynes’s sympathies really lie. It’s not necessarily a flattering portrait of Dylan we get when we puzzle together all the pieces here, but it’s a complex one, full of intra- and extra-textual references to and quotations from American culture, ’60s politics, and films of the period.

You have to admire the sheer audacity of Todd Haynes in making such a risky and difficult film that challenges rather than panders to its audience. J. Hoberman in the Voice has already called it “the movie of the year.” My favorite quote, however, comes from John Anderson of Newsday, who writes, “But ‘I’m Not There’ also takes its audience across a Rubicon of moviegoing disillusionment, apathy, and sloth: If you are, as you say, so tired of the old, then here is the new. Embrace it, or please shut up.”